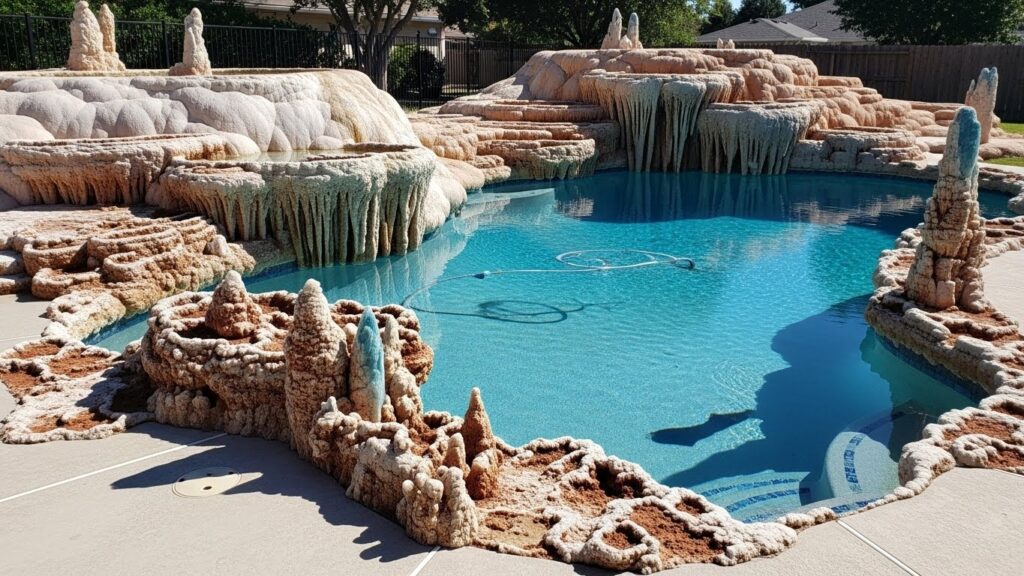

There is a distinct irony to living in the Texas Hill Country. We move here for the rugged beauty of the limestone bluffs, the crystal-clear rivers running over bedrock, and the feeling of living on top of the stone. But for anyone who owns a swimming pool, that same stone is a relentless enemy. It is trying, quite literally, to reclaim your backyard.

If you have ever looked at the waterline of your pool and seen a stubborn, crusty white ring that defies scrubbing, you are witnessing a geological event. It is not salt. It is not mold. It is liquid rock precipitating out of your water and turning back into solid rock.

This phenomenon is the result of the region’s unique hydrology. Most water in the area is drawn from the Trinity Aquifer or similar karst formations. For thousands of years, this water has filtered through massive beds of limestone and dolomite, dissolving calcium and magnesium along the way. By the time it flows out of your garden hose to fill your pool, it is saturated with minerals.

In pool chemistry terms, this is measured as Calcium Hardness. The national standard for a swimming pool suggests a hardness level between 200 and 400 parts per million (ppm). In the Hill Country, tap water often comes out of the ground at 400 ppm or higher. Essentially, your pool starts its life with a full backpack of heavy minerals, and the chemistry battle begins on day one.

The Physics of the “Heat Check”

Why does this matter? Because calcium behaves differently than almost any other substance we encounter in daily life.

Most solids, like sugar or salt, dissolve better in hot water. If you heat up tea, the sugar melts instantly. Calcium has the opposite property: Inverse Solubility. As water gets hotter, calcium becomes less soluble. It wants to separate from the water.

This creates a specific nightmare for pool equipment. The hottest points in your pool system are the heat exchanger inside your heater and the electrolytic plates inside your salt cell.

When the calcium-rich water hits these super-heated components, the calcium instantly drops out of solution and plates onto the metal. It forms a rock-hard layer of scale (calcium carbonate). This scale acts as an insulator. Inside a heater, a layer of scale the thickness of a sheet of paper can reduce efficiency by 10%. As the layer grows, the heat cannot transfer to the water, causing the heater to overheat and destroy itself.

This is why so many heaters in the region fail prematurely. They aren’t broken; they are suffocated by stone.

The Salt Cell Paradox

For owners of saltwater pools, the struggle is even more acute. A salt chlorinator works by sending electricity through metal plates to convert salt into chlorine. This process generates heat and a localized high-pH environment inside the cell—the two perfect triggers for scale formation.

In high-calcium environments, salt cells can become bridged with white crust in a matter of weeks. When the plates are coated, they stop producing chlorine. The pool owner tests the water, sees zero chlorine, and assumes the cell is broken or the salt level is low. They dump in more salt (which does nothing) or buy a new $800 cell, when the reality is that the cell was simply “petrified” by the water.

The LSI Solution: Balancing the Unbalanceable

So, if you cannot remove the calcium (unless you pay to truck in soft water, which is prohibitively expensive), how do you stop the stone?

You have to change the way you manage the water’s balance. You have to stop looking at individual readings and start looking at the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI).

The LSI is a formula that calculates the water’s true appetite for minerals. It weighs pH, alkalinity, calcium hardness, water temperature, and total dissolved solids (TDS).

- Negative LSI: The water is “aggressive.” It is hungry for calcium and will eat your plaster or corrode your metal to get it.

- Positive LSI: The water is “overfed.” It cannot hold any more calcium, so it deposits it as scale on your walls and pipes.

- Balanced LSI: The water is content.

In the Hill Country, because the Calcium Hardness is permanently high (pushing the LSI up), you must suppress the LSI by keeping the other variables lower than national averages.

Specifically, this means running a lower pH and a lower Total Alkalinity. While a pool manual in New York might say a pH of 7.6 is fine, in a high-calcium Texas pool, 7.6 might trigger scaling. You might need to keep the pH closer to 7.4. By keeping the water slightly more acidic, you force it to hold onto the heavy calcium load, preventing it from sticking to your surfaces.

The “Drain and Refill” Trap

Many frustrated homeowners attempt to solve the problem by draining their pool and refilling it, hoping to start fresh. This is often a trap.

Unless you are trucking in reverse-osmosis filtered water, you are refilling the pool with the exact same limestone-rich aquifer water that caused the problem. You reset the cyanuric acid and the salt levels, but the calcium load returns immediately.

Furthermore, evaporation makes it worse over time. When water evaporates from your pool in the brutal Texas summer, only pure H2O leaves. The minerals stay behind. Every time the auto-fill kicks on to top off the pool, it adds more calcium. Over five years, a pool that started at 400 ppm can easily drift to 800 or 1000 ppm. At those levels, the water becomes unmanageable; it feels gritty on the skin and looks dull, no matter how much you filter it.

The Role of Sequestering Agents

The final line of defense is chemical “jackets.” Products known as sequestering agents are liquids that bind to free-floating minerals. Imagine putting a microscopic straightjacket on every calcium ion. The calcium is still there, but it can’t grab onto the wall or the heater element.

In this region, a maintenance dose of a high-quality sequestering agent is not a luxury; it is a necessity for protecting the investment.

Conclusion

Owning a pool in the Hill Country requires a shift in mindset. You are not just managing sanitation; you are managing geology. The white ring on the tile is a reminder that the aquifer is always present, always pushing the chemistry toward the stone age.

The key to a crystal-clear, long-lasting pool isn’t just skimming the leaves; it’s understanding the invisible weight of the water itself. By respecting the LSI and treating the mineral content as a constant variable, you can keep the limestone in the ground where it belongs, and keep your Kerrville swimming pool looking like a sanctuary rather than a science experiment.